Skin cancer tissue rapidly identified during surgery

23 September 2013

The University of Nottingham has developed an accurate technique to rapidly identify the margins of cancerous tissue during surgery that combines auto-fluorescence of skin tissue with Raman laser spectroscopy.

The developer team, led by Dr Ioan Notingher in the University's School of Physics and Astronomy, is now looking to build an optimised instrument that can be tested in the clinic. The research has been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Dr Notingher said: “By refining our prototype instrument to make it more user-friendly and even faster to use. Diagnosis of each tissue layer could be obtained in just a few minutes — rather than hours. Such developments have the potential to revolutionise the surgical treatment of cancers. This technology will provide a fast and objective way for surgeons to make sure that all the cancer cells have been removed whilst at the same time preserving as much healthy tissue as possible.”

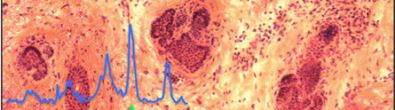

Pathology specimen showing skin cancer cells

Typically, skin conserving surgery involves cutting away one thin layer of tissue at a time and carefully examining it to make sure that all the cancer has been removed. The key is to make sure all the cancer is removed while preserving as much healthy tissue as possible to reduce scarring and disfigurement.

Dr Notingher said: “The real challenge is to know where the cancer starts and ends when looking at it during an operation so that the surgeon knows when to stop cutting. Our technique can also diagnose the presence or absence of skin cancer in thick chunks of skin tissue, making it unnecessary to cut the tissue up further into thin slices.”

A step forward for BCC

One particular technique, known as Mohs surgery — microscopically controlled surgery — is used for the treatment of difficult cases of a type of skin cancer called basal cell carcinoma (BCC). BCC is the commonest cancer in humans with more than 60,000 new patients diagnosed each year in the UK.

Mohs surgery provides the highest cure rates for BCC, but the procedure takes a lot of time because each new tissue layer has to be frozen and examined during the operation. Typically, this takes around 1-2 hours per layer so an operation can take as long as five to seven hours in total. So, from a patient’s perspective, there is a need to reduce the Mohs surgery time by developing faster and objective ways of seeing whether the cancer has been completely removed during a shorter operation under a single local anaesthetic.

Dr Notingher said, “Our technique does not rely on time consuming and laborious steps of tissue fixation, staining, labelling or sectioning. The beauty is that it can be automated and very objective. To make this new technique suitable for use in the middle of an operation such as Mohs surgery for BCC, we have combined tissue auto-fluorescence, which is quick and good at picking out all the cancer cells (but not at excluding normal tissue) as a first step, followed by Raman scattering, [which is] rather slow but good at separating normal from cancer tissue. By combining these two methods into one technique, high accuracy diagnosis of BCC can be obtained in only a few minutes.”

Professor Hywel Williams, one of the dermatologists working in the team and Director of the Centre for Evidence Based Dermatology (CEBD) at The University of Nottingham, said, “I am now convinced that this technique is reliable and potentially fast enough to replace conventional methods that determine tumour clearance for basal cell carcinoma removed during Mohs micrographic surgery — an advance that will increase the accessibility of Mohs to many more people across the world.”

This NIHR-funded research was carried out under its Invention for Innovation (i4i) Programme in collaboration with Nottingham University Hospital National Health Service (NHS) Trust, Royal Holloway University, and the CEBD.

Reference

Kong et al. Diagnosis of tumors during tissue-conserving surgery with integrated autofluorescence and Raman scattering microscopy. PNAS, vol. 110 no. 38, 15189-15194.