Transplanting photoreceptor cells into eyes restores sight in mice

8 May 2012

Scientists at University College Loondon Institute of Ophthalmology have shown for the first time that transplanting light-sensitive photoreceptors into the eyes of visually impaired mice can restore their vision.

Loss of photoreceptors is the cause of blindness in many human eye diseases including age-related macular degeneration, retinitis pigmentosa and diabetes-related blindness.

The research, published in Nature, suggests that transplanting photoreceptors — the light-sensitive nerve cells that line the back of the eye — could form the basis of a new treatment to restore sight in people with degenerative eye diseases.

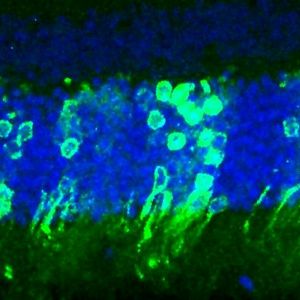

Photoreceptor cells of the eye

Scientists injected cells from young healthy mice directly into the retinas of adult mice that lacked functional rod-photoreceptors. There are two types of photoreceptor in the eye — rods and cones. The cells transplanted were immature (or progenitor) rod-photoreceptor cells. Rod cells are especially important for seeing in the dark as they are extremely sensitive to even low levels of light.

After four to six weeks, the transplanted cells appeared to be functioning almost as well as normal rod-photoreceptor cells and had formed the connections needed to transmit visual information to the brain.

We’ve shown for the first time that transplanted photoreceptor cells can integrate successfully with the existing retinal circuitry and truly improve vision. We’re hopeful that we will soon be able to replicate this success with photoreceptors derived from embryonic stem cells and eventually to develop human trials.

The researchers also tested the vision of the treated mice in a dimly lit maze. Those mice with newly transplanted rod cells were able to use a visual cue to quickly find a hidden platform in the maze whereas untreated mice were able to find the hidden platform only by chance after extensive exploration of the maze.

Professor Robin Ali at UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, who led the research, said: “We’ve shown for the first time that transplanted photoreceptor cells can integrate successfully with the existing retinal circuitry and truly improve vision. We’re hopeful that we will soon be able to replicate this success with photoreceptors derived from embryonic stem cells and eventually to develop human trials.

“Although there are many more steps before this approach will be available to patients, it could lead to treatments for thousands of people who have lost their sight through degenerative eye disorders. The findings also pave the way for techniques to repair the central nervous system as they demonstrate the brain’s amazing ability to connect with newly transplanted neurons.”

Dr Rachael Pearson from UCL Institute of Ophthalmology and principal author, said: “We are now finding ways to improve the efficiency of cone photoreceptor transplantation and to increase the effectiveness of transplantation in very degenerate retina. We will probably need to do both in order to develop effective treatments for patients.”

Dr Rob Buckle, head of regenerative medicine at the MRC said:“This is a landmark study that will inform future research across a wide range of fields including vision research, neuroscience and regenerative medicine. It provides clear evidence of functional recovery in the damaged eye through cell transplantation, providing great encouragement for the development of stem cell therapies to address the many debilitating eye conditions that affect millions worldwide.”

The researchers demonstrated previously (2010), in another study published in Nature, that it is possible to transplant photoreceptor cells into an adult mouse retina, provided the cells from the donor mouse are at a specific stage of development — when the retina is almost, but not fully, formed. In this study they optimised the rod transplantation procedure to increase the number of cells integrated into the recipient mice and so were able to restore vision.