Colour changing crystals indicate potential brain injury from bomb blast

9 Dec 2010

Photonic crystals that change colour on exposure to the blast from an explosion could be used to indicate the potential brain damage to people nearby.

Investigators at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine and School of Engineering and Applied Sciences have developed a colour-changing patch that could be worn on soldiers' helmets and uniforms. Future studies aim to calibrate the colour change to the intensity of exposure to provide an immediate read on the potential harm to the brain and the subsequent need for medical intervention. The findings are described in the ahead-of-print online issue of NeuroImage.

“We wanted to create a ‘blast badge’ that would be lightweight, durable, power-free, and perhaps most important, could be easily interpreted, even on the battlefield”, says senior author Douglas H. Smith, MD, director of the Center for Brain Injury and Repair and professor of Neurosurgery at Penn. “Similar to how an opera singer can shatter glass crystal, we chose colour-changing crystals that could be designed to break apart when exposed to a blast shockwave, causing a substantial colour change.”

Blast-induced traumatic brain injury is the "signature wound" of the current wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. However, with no objective information of relative blast exposure, soldiers with brain injury may not receive appropriate medical care and are at risk of being returned to the battlefield too soon.

“Diagnosis of mild traumatic brain injury [TBI] is challenging under most circumstances, as subtle or slowly progressive damage to brain tissue occurs in a manner undetectable by conventional imaging techniques,” notes Cullen. There is also a debate as to whether mild TBI is confused with post-traumatic stress syndrome. “This emphasizes the need for an objective measure of blast exposure to ensure solders receive proper care,” he says.

Nanoscale structure

The badges are comprised of nanoscale structures, in this case pores and columns, whose make-up preferentially reflects certain wavelengths. Lasers sculpt these tiny shapes into a plastic sheet.

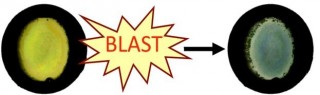

Yang’s group pioneered this microfabrication of three-dimensional photonic structures using holographic lithography. “We came up the idea of using three-dimensional photonic crystals as a blast injury dosimeter because of their unique structure-dependent mechanical response and colourful display,” she explains. Her lab made the materials and characterized the structures before and after the blast to understand the colour-change mechanism.

"It looks like layers of Swiss cheese with columns in between," explains Smith. Although very stable in the presence of heat, cold or physical impact, the nanostructures are selectively altered by blast exposure. The shockwave causes the columns to collapse and the pores to grow larger, thereby changing the material's reflective properties and outward colour. The material is designed so that the extent of the colour change corresponds with blast intensity.

The blast-sensitive material is added as a thin film on small round badges that could be sewn onto a soldier's uniform.

In addition to use as a blast sensor for brain injury, other applications include testing blast protection of structures, vehicles and equipment for military and civilian use.