Magnetic resonance imaging shows what people store in short-term memory

15 March 2009

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), can show what information people are holding in memory based only on patterns of activity in the brain.

Psychologists from the University of Oregon and the University of California, San Diego, reported their findings in the February issue of Psychological Science. By analyzing blood-flow activity, they were able to identify the specific colour or orientation of an object that was intentionally stored by the observer.

The experiments, in which subjects viewed a stimulus for one second and held a specific aspect of the object in mind after the stimulus disappeared, were conducted in the UO's Robert and Beverly Lewis Center for Neuroimaging. In 10-second delays after each exposure, researchers recorded brain activity during memory selection and storage processing in the visual cortex, a brain region that they hypothesized would support the maintenance of visual details in short-term memory.

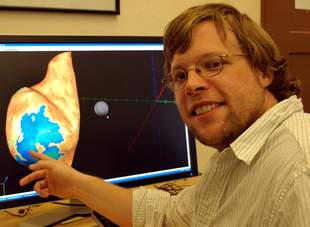

University of Oregon doctoral student Edward Ester

points

to a rendering of the brain's visual cortex on a computer

screen display, where areas of brain activity are shown.

"Another interesting thing was that if subjects were remembering orientation, then that pattern of activity during the delay period had no information about colour, even though they were staring at a colored-oriented stimulus," said Edward Awh, a UO professor of psychology. "Likewise, if they chose to remember colour we were able to decode which colour they remembered, but orientation information was completely missing."

Researchers used machine-learning algorithms to examine spatial patterns of activation in the early visual cortex that are associated with remembering different stimuli, said John T Serences, professor of psychology at UC-San Diego. "This algorithm," he said, "can then be used to predict exactly what someone is remembering based on these activation patterns."

Increases in blood flow, as seen with fMRI, are measured in voxels — small units displayed in a 3-D grid. Different vectors of the grid, corresponding to neurons, respond as subjects view and store their chosen memories. Based on patterns of activity in an individual's visual cortex, located at the rear of the brain, researchers can pinpoint what is being stored and where, Awh said.

The study is similar to one published this month in Nature and led by Vanderbilt University neuroscientist Frank Tong and colleagues, who were able to predict with 80% plus accuracy which patterns individuals held in memory 11 seconds after seeing a stimulus.

"Their paper makes a very similar point to ours," Awh said, "though they did not vary which 'dimension' of the stimulus people chose to remember, and they did not compare the pattern of activity during sensory processing and during memory. They showed that they could look at brain activity to classify which orientation was being stored in memory."

What Awh and colleagues found was that the sensory area of the brain had a pattern of activity that represented only an individual's intentionally stored aspect of the stimulus. This voluntary control in memory selection, Awh said, falls in line with previous research, including that done by Awh and co-author Edward K. Vogel, also of the UO, that there is limited capacity for what can be stored at one time. People choose what is important and relevant to them, Awh said.

"Basically, our study shows that information about the precise feature a person is remembering is represented in the visual cortex," Serences said, "This is important because it demonstrates that people recruit the same neural machinery during memory as they do when they see a stimulus."

That demonstration, Awh said, supports the sensory recruitment hypothesis, which suggests the same parts of the brain are involved in perception of a stimulus and memory storage.

A fourth co-author with Awh, Serences and Vogel was Edward F Ester, a UO doctoral student. Serences was with the University of California, Irvine, when the project began. The research was primarily funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health to Awh, and by support from the UO's Robert and Beverly Lewis Center for Neuroimaging.

Bookmark this page