| Oncology, diagnostic imaging | |||

Imaging technology identifies compounds that can fight tumours21 July 2006 Using a newly developed drug screen, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine have discovered small-molecule compounds that are able to perform the functions of a gene commonly mutated in many types of cancer. By combining molecular imaging techniques with human cancer cell culture and animal model approaches, the researchers were able to reveal the ability of the compounds to kill human tumour cells.

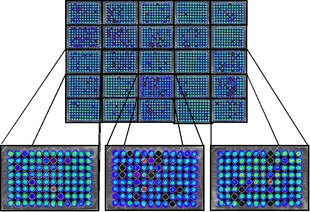

These findings emphasize the growing role of imaging technology in aiding researchers in the development of individualized cancer treatments. p53, a tumour suppressor gene, is widely mutated across all types of cancer. In addition to causing aggressive tumour growth, a mutation in the p53 gene contributes to chemotherapy and radiotherapy resistance. In search of methods to combat treatment-resistant tumours, Wafik S. El-Deiry, MD, PhD, Professor in the Departments of Medicine (haematology/oncology), Genetics, and Pharmacology, and colleagues employed molecular imaging techniques to evaluate the ability of small molecules to produce normal p53 function in the p53-deficient and p53-mutant cancer cells. They report their findings in the most recent online issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. In an attempt to defend the body, a normal p53 protein will bind to DNA during periods of cellular stress or damage. The binding of p53 to DNA initiates downstream reactions that keep the stressed cells from multiplying. Under normal conditions, p53 will activate the p21 gene, causing the cell cycle to freeze, halting cell proliferation; p53 will activate KILLER/DR5, which signals for cell death, or apoptosis. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy set out to deliberately stress tumour cells in hopes of promoting their self-destruction. Unfortunately, mutations to the p53 gene disrupt the intracellular defence system. “Mutants of p53 that occur in human cancer fail to bind to DNA or to activate target genes, such as p21 and KILLER/DR5,” explains El-Deiry, who is also the Co-Program Leader of the Radiation Biology Program at the Abramson Cancer Center at Penn. “Therefore, when cells are stressed or damaged, p53-mutant cells fail to shutdown and continue to divide uncontrollably.” The development of a drug screen by El-Deiry’s lab allowed the researchers to trace the activity of small molecules in p53-mutant cancer cells. The small-molecule drug screen, developed by El-Deiry’s lab, was created by inserting firefly luciferase, a reporter gene capable of emitting light, into human tumour cells carrying the p53 mutation, and observing the subsequent response. “Just as fireflies emit light that we can see with our eyes, the cancer cells were engineered to emit light if a p53-like response was triggered by any of the small molecules that we examined,” explains El-Deiry. The small molecules screened by El-Deiry’s research group were obtained from the Developmental Therapeutics Program at the National Cancer Institute. The molecules represent many classes of compounds and include both natural and man-made chemicals. “One by one, we introduced the small molecules to the p53 mutant cancer cells, which possessed the luciferase reporter gene and screened for light emissions,” describes El-Deiry. The light emissions displayed by the live cell imaging instrumentation revealed which molecules were able to achieve p53 responses in the abnormal cancer cells. Further testing exposed the ability of high doses of several groups of the small molecules to kill human cancer cells in cell culture and in mouse models implanted with human tumours. “Our work provides a blueprint for how molecularly targeted therapy can be discovered using new optical imaging technology,” states El-Deiry. “This is very important going forward in the era of molecular medicine and individualized therapy for cancer patients.” In the future, El-Deiry plans to continue to explore the therapeutic effects of the small molecule compounds in different types of cancer and to evaluate the potential toxicities of these compounds. Ultimately, El-Deiry’s research group hopes to bring new anti-cancer agents to the clinic. In a review paper published this week in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, El-Deiry addresses the importance of molecular imaging in the future of oncologic drug discovery and development. “With the advancement of molecular imaging, we have the capabilities to develop strategies that will target the molecular alterations in cancer and to closely examine how drugs bind to their respective targets in cancer patients,” says El-Deiry. “This will help doctors to understand why anti-cancer drugs work when they do work and fail when they fail.” By allowing for better patient selection and treatment monitoring strategies, molecular imaging will likely reduce the future cost of drug development, he predicts.

|